Confessions of a Quarter Centenarian

中文版請點這裡。

1. His Name Is E.C.

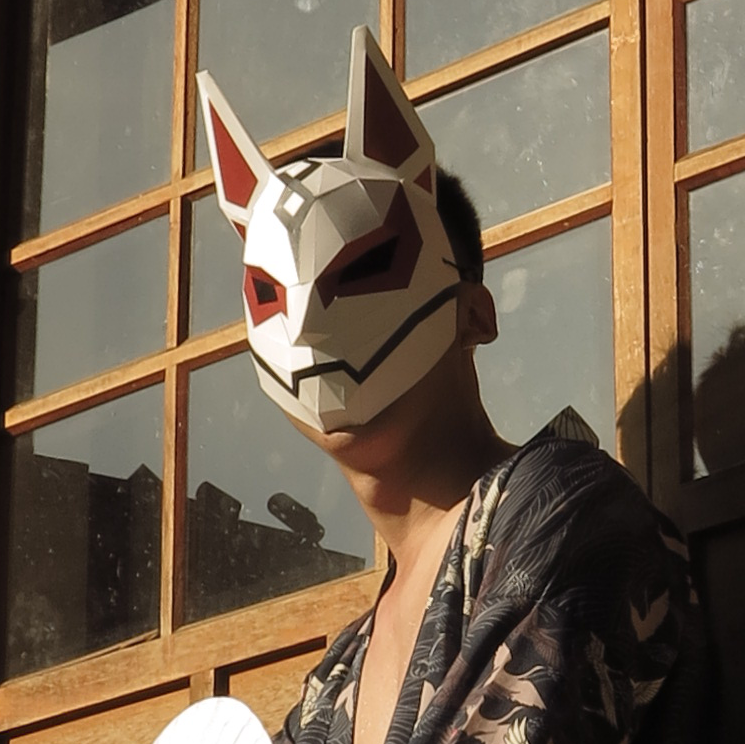

There’s this guy that has been preying on my mind for a while now. He’s not a friend, nor an acquaintance; I’d describe him as a mere stranger that I simply have known existed for an extended period of time. Our very limited correspondence justify the fact that I can’t recall what he looks like, though if I were to wager a guess, he’d be a thin, attractive figure, dressed in dancing shadows and cloaked in an aura of mystery. He’d have a hood pulled over his head, but that wouldn’t be near enough to conceal the bright light that emanates from his eyes, from which you could see the cosmos and the reflections of countless stars.

A brilliant and handsome being, yet the way he speaks terrifies me—in silent whispers, in hushed tones, his voice kind but firm, his each and every word forcing me to think in quantities and time frames that my brain cannot comprehend. Like a drop of water in oceans mighty, a grain of fine sand on wave-swept shores, when he speaks, I realize the insignificance of everything that makes me me—my thoughts, ideologies, and beliefs. He makes me question the very meaning of existence.

It’s a bit overwhelming to think about. Which is the precise reason why he’s been nothing but a stranger all these years. I’ve avoided him whenever I can.

His name is Existential Crisis. Dude just can’t have a more common name like James or John or David. A bit of a mouthful, if you ask me, so I just call him E.C. But more on him later.

2. An Invitation

Perhaps you’ve heard of the term “birthday blues.” Wikipedia describes it as “a statistical phenomenon where an individual’s likelihood of death appears to increase on or close to their birthday.” A bit morbid, perhaps, but I think I understand it. I’m not vouching for the scientific accuracy of the studies behind this phenomenon, and nor do I speak for anyone else here, but I do usually experience some degree of anxiety on or around my birthday. I haven’t, however, heard anyone explicitly mention that they feel the same.

Don’t be concerned about my well-being. I won’t call myself physically or mentally ill, and any changes in mood that occur due to this phenomenon are largely manageable. However, there are reasons why while birthday dinners with family and friends are alright, I’ve never wanted to throw a party on my own birthday. For me, this time of year is a time to face, in a manner as candid as possible, the psychological stress and fear of falling behind in life, of wasting time, and mortality salience. ’Tis a time for self reflection, so while some might celebrate with splendid parties filled with colorful balloons, sugary pastries, and alcoholic beverages, I often just spend the night in an enclosed space in which I feel safe and comfortable, ideally with a deficient in pointy objects and with a surfeit of soft pillows and fluffy blankets.

This year though, surprise!—I’m making an exception. I’m throwing a party, but I’m inviting just one guy. I don’t know him very well yet, but I’m hoping maybe we can become friends. You can probably already guess who it is.

Like a teenage boy who’s sent his first confession via text, I’m eagerly awaiting his response, and if he says yes, I look forward to blasting some acoustic slow pop on Spotify and having a great night as the clock strikes twelve on my birthday eve.

3. The Infinite Abyss

Guess what? E.C. said yes.

He does have a penchant for making unexpected entrances though. I was just lying in my bed the other night, watching the same TikTok for the sixteenth time and admiring how absolutely stunning human creativity can be when I turned my head and, lo and behold, there he was, on my already-cramped-enough single bed, his face mere inches away from mine.

It always starts like this, an unplanned encounter in highly intimate proximity, looming in the air the uncomfortable possibilities of learning something new about myself. I feel his warm breath on my nose. If I deny interaction, I know from experience that he’d leave silently after some time has passed.

This time though, I resist the initial urge to pull away. “Oh. Hey there,” I mumble, and I stare into those eyes of his.

It’s like staring into a deep abyss. At first I’m seeing only bottomless darkness, containing within it infinite uncertainties. Anything could be in there, or nothing at all, and that makes it all the more intriguing. So I end up putting part of myself in the abyss, slowly at first: a finger, a hand, an arm, and the next thing I know, I’m letting myself be swallowed, and I’m falling, falling, falling…

Everything is dark at first. But then there are these speckles of flame, which turn out to be stars, and I use everything at my disposal to make sense of them. One doesn’t communicate with E.C. using only words. Words are simply not enough. Words, sure, but also images, memories, sounds, ideas, every possible medium of data huddling together to form a glowing sphere of consciousness which is me.

And suddenly that’s when I realize I’m no longer falling. This is where the pleasantries end and the dialogue begins. I’d like to record exactly what happens in the exchange, but once I stop staring into the eyes of E.C., I forget much of that dialogue. It’s like waking up from a dream, all that happened, the excitement, the terror, the clarity, the anxiety, reduced to fleeting reminiscence and wisps of what-has-been.

The following passages derive from a strong desire to at least attempt to record part of this dialogue, hoping that these very words can guide me and help me maintain the dialogue with a clearer state of mind, lest I fall into the infinite abyss again without any preparation. If you experience negative symptoms, including mood swings, lost of appetite, or an urge to hug your friends and loved ones, you are very welcome to leave at any time.

I’ll start by describing how the dialogue always begins. It’s always the reminder of scale.

4. Everything is Mostly Nothing

Dear Reader,

If you’re currently reading these words, I assume you are both of the following: 1) alive, and 2) human. Unless the world’s been overtaken by some other apex species or robotic overlords, in which case, I’m both shocked and flattered that this piece of writing survived, Your Lordship.

If you’re alive and human (scale: meters), you’ve got the eleven organ systems in your body to thank. Organ systems are made up of organs (scale: centimeters, or 10^-2 m), and organs are in turn collections of tissues (scale: micrometers, or 10^-6 m), working together to serve some common function. Things at the scale of micrometers are the smallest things that are still visible to the naked human eye. Hair, for example, composed of mainly dead tissue, has a diameter of around 100 micrometers. Individual cells that make up tissue are only visible to us via the aid of a microscope.

The human body is made up of 30-40 trillion cells, each of which are just as alive as we are and can exist on their own, indifferently proclaiming the title of “the smallest structural and functional unit of living organisms.” In the brain of each cell, the nucleus, we find DNA molecules packaged into thread-like structures called chromosomes. These DNA molecules (scale: nanometers, or 10^-9 m) supply the genetic instructions of life, serving as the operating system on which living creatures run, commanding everything from development to reproduction. At this scale, sizes are smaller than the wavelengths of visible light (380-740 nanometers), and seeing in any meaningful human way proves impossible. Thus, we must rely on waves with shorter wavelengths as we employ atomic vision to begin to see the smallest unit of ordinary matter: atoms (scale: picometers, or 10^-12 m). Atoms of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus, hexagonally arranged in a wonderfully intricate manner to create the state of existence both fascinating and generally taken for granted.

As we unveil the electron orbitals of an atom and take a peek at what’s inside, we discover the fundamental truth of life and matter.

Everything is made of mostly, nothing.

Take the hydrogen atom. At the center of the atom lies but the tiniest speck of matter: a single proton 1/100,000 the size of the atom that contains it. The other 99.999% is nothing, just empty space, electron clouds that indicate the probability of maybe, just maybe, finding something. Atoms that are 99.999% made of nothing create the illusion of everything that you will ever see, feel, or love.

But enough with small things. To have a comprehensive understanding of scale, we must go both ways. So we zoom out and out until you find you in your average-sized human body, living inside an average-sized house (scale: meters).

To leave the country, we can hop on a commercial airplane, one with a velocity of approximately 15 kilometers per minute. But to leave the earth, we must do better than a plane.

Let us pretend that human civilization has advanced enough to create a vehicle that is light speed (~300,000 km/second), the fastest speed known to man in the universe. A second at light speed is enough to go around the Earth seven and a half times.

The distance from Earth to the nearest other object, her moon, is 384,400 kilometers. That’s a little bit more than 30 Earth diameters away. To our home star, the Sun, the distance is 149,000,000 kilometers away, otherwise known as 1 astronomical unit (AU).

With our light-speed vehicle, it would take 1.3 seconds to get to the moon, and eight minutes, enough to brew a nice hot cup of coffee and sit down and watch a few memes, for us to reach our home star, the Sun.

To reach the edge of our inner solar system, we’d have to travel 456 million kilometers, which takes around 25 minutes. The diameter of the solar system is 9 billion kilometers, so to reach the edge of the outer solar system and to visit Neptune, it’ll take us eight hours, enough for a good night’s sleep.

With our light-speed vehicle, traveling in our solar system is comparable to traveling by plane on Earth. However, at the scale of all that exists our solar system is nothing. As we leave the gravitational bound system of the Sun, it will not be long until the speed of light proves disheartening slow.

Our solar system’s nearest neighbor star, Proxima Centauri, will take a vehicle the speed of light 4 years to reach. Our stellar neighborhood is around 30-40 light years across, and the Milky Way galaxy, a collection of 100 billion stars shining in the dark, is around 100,000 light years (100 millennia) across.

This is where it all starts to become incomprehensible.

The Milky Way is but one galaxy in an infinite number of galaxies. Our local group, which consists of around 30 galaxies, is 10 million light years in diameter. The Laniakea supercluster, home to the Milky Way and around 100,000 other nearby galaxies, is 500 million light years in diameter. The observable universe has an estimate of 10 million superclusters, a sphere containing 2 trillion galaxies, and its size is by definition the speed at which light travels for as long as the universe has existed. And then there is the unobservable universe, in which exists objects so distant that light anywhere within it will never reach Earth before the death of every living thing everywhere, including the death of the universe itself.

So, as our vehicle speeds on through interstellar space at the speed of light, you look out the shuttle window and find to your dismay that the universe is not at all the festive collection of stars like you imagine. In fact, it’ll mostly likely be years apart at light speed before you see another singular star out in the dark void.

The universe is empty and lonely, and thus, we get to the truth of the universe.

Everything is made of mostly, nothing.

At scales both big and small, for both atoms and for the universe, nothing makes up most everything. And when nothing is everything and everything is nothing, what is left?

Moral: The next time my high school bully walks up to me and spits at my face, telling me, “You are nothing,” I’ll just give him a sad smile and retort, “You are, I must admit, scientifically accurate.”

5. The Game of Life

Ah, the game of life. The game that everyone alive plays, whether they want to or not. I started my run a quarter-century ago.

When you unbox the game, there’s the main game board, and the rules printed on a card with intricate lettering.

The game of life has highly unsophisticated rules. Everyone plays on a board with a grid of boxes. At the end of each week, you fill in one of the boxes. The game ends when you have no more boxes left.

The average board has 4,160 boxes, drawn on a 52 by 80 grid, each row representing the 52 weeks in a year of an average person’s 80-year life expectancy. Each copy is unique, however, so depending on various factors, some might get a board with more boxes, and some fewer.

This is what an average game board look like, given modern day technonlogy.

When I look at my game board, it currently looks like this:

Zooming in closer, it looks like this:

That’s the entire game. It’s precisely the simplicity of the rules that make the game frustratingly difficult. There is no winning or losing, at least not out of the box. The conditions of winning are defined by each player who plays the game, but cannot just be any arbitrary metric. Every win condition requires the silent approval of E.C., so waking up one day and deciding that you win by blinking doesn’t cut it.

Given that the game board is so simple, I spent some time decorating it with some fun colors that mark certain milestones in my past.

I think reasoning about time in this way is both eye-opening and depressing.

Humans have clawed their way up the evolutionary ladder of consciousness only to realize that one day, without fail, we’re all going to die.

Time can feel relative. The three hour wait in line at the bank just to report a lost credit card feels extremely long, and the two weeks off on vacation in the beautiful lush mountains seem unfortunately short. But looking at this board, one thing is certain — and that’s life is most definitely finite.

We are but specks of consciousness enclosed in a material human body that is ephemeral in the grand scheme of things. Death is inevitable, so humans have found ways to cope: through religion, philosophical and ethical beliefs, and lifestyle choices such as hedonism.

Death is scary. I still remember when I was still in elementary school, the occasional days on which I would just lie on my bed and picture a world in which I do not exist. The world still functions, just without me, forever and for eternity. It’s a scary thought that almost always ended in tears and numbing terror, so I’ve learned not to think about it, for the following decade or so.

Humans are given finite time, which begs the soul searching question: what gives life meaning? It’s a question that many has pondered, and one which I’ll continue to try to find the answer to, but as of current, I’m attracted to the idea of optimistic nihilism. From what I’ve read, it’s somewhat similar to the philosophical belief of existentialism, but I’m not here to define nomenclature. Here’s my understanding of what I believe in:

Optimistic nihilism acknowledges that life in itself lacks both meaning and purpose. The Game of Life, out of the box, provides only the game board and the simplest of rules (e.g., time limitations). It’s the understanding that the universe doesn’t care about you and, in the grand scheme of things, you’re less than just a speck of dust in cosmic vastness. You, are in fact, mostly nothing (see Everything is Mostly Nothing), and to think that you are assigned meaning at birth is to greatly overestimate your own significance.

The “optimistic” in optimistic nihilism comes from a change in mindset, understanding that the inherent lack of purpose is not depressing, bur rather, liberating. It means everyone is free to choose their own purpose, like a choose-your-own-adventure book. I’ve decided on a few life themes for now that I’m going to pitch to E.C. for approval, and I hope to find at least some meaning through the pursuit of these themes. It seems that with clearer goals in mind, our brains’ incapability to comprehend sizes and time frames becomes more an asset than a liability—for I am able to focus on the present and the foreseeable near future in which I am still alive rather being paralyzed by my own ephemerality.

I’m riding a bike down a dark road. I know it ends in an inevitable, lethal fall down a cliff. But I keep riding anyway, without an inherent reason, armed with the knowledge that I’m only able to be here due to millions of years of evolutionary complexity.

So, I’m going to enjoy the view on the ride, and appreciate all the nice things and great people I meet along the way. And when the time comes, perhaps eternity will not be as scary as it seems.

6. Touch of Midas: The Life Theme of Money

If obsession is simply the domination of one’s thoughts by a persistent idea, then at some point between matriculation and graduation, I went from being happily oblivious to most fiscal matters to being quietly obsessed with money. Or to be more precise, money as a store of value. If most jobs are in essence an act of trading time for money (ignoring, for now, additional benefits such as fulfillment and self improvement), and I’ve already established my view that time is the ultimate resource (see The Game of Life), then by consequence it makes sense to understand to what degree is money worth pursuing.

I think becoming fully independent (at least in financial aspects) is, among other things, one of the more tangible differences between being a student and a working member of society. As the tides of adulthood come crashing down with fiscal responsibilities and with no one but myself to hold accountable, money became something I thought about on a daily basis, a static noise in the background, buzzing in my brain every time I opened my wallet, withdrew cash from an ATM, or hovered plastic. Can I afford rent? Is this purchase worth it? Single ply or double ply toilet paper (cause single ply is cheaper)?

I went from only thinking “save money put in bank good”, to finally figuring out my net worth, my expenses and debts, learning about simple financial instruments, and purchasing my first securities.

I also started noticing people talking about money all around me: the squad leaders debating over what to do with their lifetime renumeration after being in service for over 20 years, the colleague sitting diagonally across from me at work casually trading Bored Ape NFTs worth 300,000 USD, the lifeguards at the pool discussing stock predictions and call options.

It’s in all the little things too—the restaurants that former classmates pick out at a reunion, and and as people start showing up, the clothes that she wears that not-so-subtly screams designer, and the new Tesla that he nonchalantly pulls up into the parking lot.

I watched as friends and acquaintances step into their respective, esteemed fields, becoming doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, performers, artists, creators, and entrepreneurs. And sometimes it feels like they’ve hailed an Uber and sped off into the golden sunset while I’m still on my way to the bus station, clutching my year pass in hand.

It is perhaps illogical and unproductive to compare ourselves to those around us, and if we do, the downward spiral begins, but sometimes we do it anyway. And when it comes to money, mood swings come fast and often—I witnessed this firsthand by lurking in the r/wallstreetbets subreddit and NFT project discords when cute animal PFPs were all the hype. When you make money, adrenaline rushes in and you feel invincible; when you lose it, the world comes crashing down.

Money is just one life theme, out of many. It all comes back to the question. What do I want? How much is enough?

There’s a framework for thinking about money in levels proposed by @punk6529 on Twitter that I think has been highly helpful to me and have in large parts adopted as my own framework. It helps me filter any senseless negative emotion like greed and envy to focus on where I am and where I want to be at a certain point in the future.

The levels are as follows:

Level 1: Crushed by Circumstance

Although statistics vary, The World Bank estimates that around 10% of people in the world live in extreme poverty.

These people suffer from circumstances that are outside of their control, among which are systemic failure such as lack of clean water and lack of medical resources, natural disasters like recurrent droughts and floods, and man-caused catastrophes including warfare and coronavirus.

Level 1 is in many cases a coordination problem. While many will be willing to sacrifice pocket change in return to save a kid’s life, there are no effective systems to reallocate resources from those with excess to those in need. We can only hope as humanity progresses as a whole, so too does the proportion of people stuck in Level 1 decrease.

Level 2: The Struggle is Real

The expenditures of daily life in order to maintain a minimum quality of living proves to be a huge headache at this stage. A place to live, mouths to feed. People in Level 2 take on multiple jobs but still do not have any savings. They worry about an emergency of any form, for an inopportune mishap could invoke a cascading series of problems due to not having extra money to fix the problem.

6529 mentioned in his post that many people are or have been in Level 2 at some point in their lifetime. He also suggests Level 2 people do everything in their power to move up to Level 3. When money problems are the front and center of life, they impose a huge tax on one’s happiness and effectiveness. At this stage, money has a fundamentally positive effect. With a modicum of financial success, the degree to which a person’s general anxiety declines can be exponential.

Level 3: A Happy Place

Though broad is the ranges of income, dependent on local and global economies, for Level 3, Level 3 people share similar “middle class” living experiences that can be defined. They have a house, or don’t worry about having a place to live. They can afford to eat when hungry, and rest when tired. They have some amount of savings in case of emergencies. They have some amount of money that can be used for entertainment, hobbies, and investments.

Level 3 is a happy place, with beautiful scenery and a comfortable standard of living. On a bad day, Level 3 people work overtime and complain about the rain, but on a good day, they’d go to a theater and eat out at a fancy restaurant. It’s said that many who reach Level 3 stays here, for a prolonged duration, perhaps even a lifetime.

Level 4: The Consumerist Playground

From the upper-end of the middle class to owners of luxurious mansions guarded by acres of private beaches and fabulous rainbow unicorns, Level four people have the basic consumption needs of everyday life well sorted out and can now, to their heart’s content, start enjoying the material things.

A private jet. A summer condo. A trip around the world. In the vast consumerist playground filled with shiny new toys and excitement, money buys everything that money can buy.

We’ve all seen depictions of the uber-rich in movies, and probably all had that dream at least once — sprinkling stacks of bills from a helicopter like putting sprinkles on an ice cream sundae. The amount of wealth that the richest people on Earth has is remarkably impressive, as you can see here in Wealth Shown to Scale.

The Bonus Level

The bonus level, as its name implies, is less about reaching a specific amount of money than some state of satisfaction in which one’s consumption needs are met.

For me, I’d like to think about it as having enough money, enough defined as any amount equal or greater than that needed such that money is no longer a hinderance to any of my other life themes. It means going from a pursuit of survival to a pursuit of passion.

It means be able to choose healthier food options despite the fact that they cost ten times as much than instant instant noodles and bread (life theme: health). It means not taking on a job that leaves me both physically and mentally exhausted just because it pays well (life theme: happiness). It means being able fly to another country to visit some friends that I would love to catch up with given the opportunity (life theme: relationships). It means being able to acquire the necessary equipment and resources for projects and ideas that I hope to implement (life theme: fulfillment). It means having the freedom to choose.

Alas, meet the doppelgängers. The normal Him, and the golden Him.

The Normal Him is primarily motivated by his interests and desires, and he does the things that he finds important or simply makes him happy — spending time with family, binge watching Netflix, or out in the wild hunting a golden stag.

The golden Him is primarily motivated by money, and monetary value and incentive are the dominant criteria which he uses to make decisions. He’d take the job that he despises because it pays more, he’d give up sleep for his side hustles, and if a time machine was invented, the first thing he’d think of doing is buying a lottery ticket that he knows the winning numbers of.

If the values of Golden Him happens to align with Normal Him, e.g., he’s losing sleep over his side hustle and he’s hustling to make more money, but in the process he’s learning people skills, feeling fulfilled, and creating long term value, then all is well and good. But when their priorities misalign, the ground of The Bonus Level cracks and shatters and both of them fall through, landing back on whatever level they were on to begin with.

Maybe the bonus level is unobtainable because they say a person’s desires and wants grow in accordance with the amount of money they have. Perhaps with ten times the income, a person’s idea of a relaxing day would shift from cycling along the riverbed to flying a charter into the Caribbean, which cost a hella lot more. I wouldn’t know, since I haven’t reached this level yet.

As of now, I think my goal is to steady myself in Level 3, prevent myself from making any stupid decisions that would cause me to fall to Level 2, and hopefully, sometimes get a glimpse of what the Bonus Level could be like. Ultimately, I’d like to be able to reach some sort of financial freedom and experience Level 4 someday, and cross the life theme of money entirely off my list. Until then, I welcome any donations in either cash or crypto to my account or the warm affection of sugar mommas and zaddies :)

7. Swipe Right: The Life Theme of Relationships

I thought about completely skipping over this theme. I feel like I’ve still just begun to learn the social skills and cues when it comes to making friends, and as for dating, hah, let’s just say what little experience I do have are somewhat atypical. So I’m staring at this blank page, squirming uncomfortably and wondering exactly what I should and shouldn’t write.

In general, besides consanguineal kinship which connects two people by blood, I think there are two other main categories of relationships––friendship (platonic relationship) and romance (romantic relationship). Though honestly, I’m not quite sure what the main difference is between the two.

One idea is that they differ by the intensity of feelings. The problem with that is the mind is highly erratic when it comes to affection (in retrospect, I have absolutely zero idea why my crush was who it was in middle school), and the body is highly superficial and responds primarily to visual and other forms of stimuli when it comes to arousal (hence there are people I would absolutely smash but never consider dating.)

Another idea is that they differ by the deliberate amount of work and effort needed to be put in. Romantic relationships by default require a higher level of openness, trust, and sharing, whereas there are no terms of existence for friendship and friendship can function with a low level of openness. The problem with that is, I’m not fully convinced it’s true. Seems to me that all the qualities mentioned above are also required in close friendships and are therefore not exclusive to romance.

So, maybe I don’t know what I’m talking about. Just throwing some ideas out.

Let’s talk friendship first.

I think relationships/friendships are kind of like containers. For ease of explanation, let’s pretend that they are oil tanks. Every time you ask for a favor, or otherwise invoke your friend as a form of resource, you use up a little bit of the oil in their tank. So have them fix your computer, use their Costco membership card, and complain to them about your terrible day over the deafening music at the bar, but be warned, once that tank empties, they will no longer consider you their friend.

Of course, there are ways to refill that tank, one of which is returning favors, or more generally, do for them what they will be willing to do for you when they need it. Also, with quality time spent together, you can upgrade to bigger tanks that hold even more oil.

As the containers’ capacities increase, so too does the appropriate ranges of favors to ask. For instance, it would generally be considered a burden if a classmate you barely talk to in class asks to copy your homework, or if the neighbor you’ve never met wants you to help walk her dog. It’s like how you wouldn’t respond to a friendly waiter’s “How’s your day going,” with an honest “Terrible, my grandparent just passed away.” Yet, these behaviors are generally accepted, or perhaps even become second nature, when the relationship between the two people strengthens.

After some self reflection, I think my problem with not being the best at making friends come from these issues: 1) I subconsciously find maintaining a large amount of small containers exhausting and of little merit, especially those which I have no interest in ever expanding their capacities, and 2) I don’t engage enough or open myself enough in situations during which the capacities of containers are usually increased. I’m working on myself though, and hopefully I get better with practice.

Okay, now comes the dreaded part where we talk romance.

I sometimes worry that my perception of intimacy is so skewed that talking about it can cause others to question my character. Yet perhaps there is nothing such as typical when it comes to romantic affection, for love is as messy as can be, wrought with human emotion that in those instants often trump logic.

There have been some people (hopefully real and not imaginary), both male and female, who have asked to date me, but I had never explicitly said yes due to a variety of reasons. I’ve also confessed to a small handful of people, though in retrospect, I cannot tell you what my thought processes were. I had some intimate experimentations with select friends that subsequently resulted in awkward but agreeable silence. I’ve experienced a minor heartbreak during which I rushed to an instrument store to buy a guitar just so I could learn the minor chords. I’ve had my fair share of hookups, but those tend to be as NSA as possibly can be.

So yeah, a pretty bland resume with a not a whole lot of “typical dating”, but hear me out:

Teachers don’t expect students to do well in hard subjects without studying. You don’t expect to pick up a new language and suddenly become super proficient. The same goes for literally any other skill in the world, where practice and continued effort is a prerequisite of good performance and expertise.

So how is it that when it comes to love, a language as convoluted as the range of human behavior is complex, society generally expects proficiency in all the positive and moral attributes: good communication, honestly, compromise, commitment, while the acts associated with “practicing romance” are generally frowned upon? That includes changing partners (with some level of frequency), causal hookups and sex, and being intimately engaged with multiple people simultaneously without explicitly partnering up with any one of them.

In my imagination, it goes one of two ways:

-

I follow social norms and date a single individual. The relationship takes years, and of course problems arise, but we work it out. But then, something happens where neither side is willing to back off. When it all goes south, I realize that I’ve never tried any other relationships at all. I also realize that I’ve spent too many years with one person and end up convincing myself that love is a prime example of human endeavor that is meaningless and only results in utter disappointment.

-

I simultaneously date a hundred people as a test run. I fuck up in some of them, but in others, it goes at least somewhat smoothly. With the data collected, I figure out what I want and what I can offer. With this new set of criteria that I acquired at the risk of seeming like an incorrigible womanizer, I become much more proficient with romantic endeavors and can make better decisions with that all that practice.

I don’t know, but out of the two options I vibe with the second one a bit more.

Of course, I don’t go to the extreme lengths as portrayed in the option, but I did spend a few months playing with a handful of dating apps and having conversations with hundreds of people (can you even call those conversations?). Additionally, I’m making an effort to spend more time with people that I feel attracted to. I’ve also accepted that the dynamic of a relationship can be that it is still too early to discuss the status of the relationship, and I’ve come to accept that as the definition of the relationship and not me just being afraid to commit.

So yeah, there’s my take. And I don’t have a witty remark to end this on, so please just pretend that this is one of those Tinder conversations in which the opposing party suddenly blocks you for no apparent reason.

(Blocked. Please contact support if you think this is a mistake.)

8. The Bird Cannot Be Caught: The Life Theme of Happiness

There’s more life themes I could have written about, but given time restraints, I’ve decided to end on the theme of happiness. It’s what most people would say they want, and what some people might consider one of the ultimate goals of life.

There’s an instrument called the hedonometer that measures the level of happiness of large populations via online expressions. The hedonometer takes in people’s social media data (Twitter tweets), and estimates happiness levels via the usage of words. The actual algorithm is more complicated, but the basic idea is that all words of common occurrence in a number of languages are given a perceived happiness score from 1 (sad) to 9 (happy) via crowdsourcing. For instance, the word “laughter” has a happiness score of 8.5, “love” has a happiness score of 8.42, “pandemic” has a happiness score of 1.6, and “murder” has a happiness score of 1.48.

It’s pretty interesting; check out the hedonometer project here.

Happiness is a weird theme, for it is perhaps the only life theme that should not be actively pursued. You can try to, but there are significant diminishing returns. Thinking of happiness as a location to reach in which exists happy people who are always happy renders happiness an impossible concept that none shall attain. The range of human emotion is broad, and being happy does not mean being happy all of the time, but rather, being happy on average while still encompassing all the other valid emotions.

Happiness is like a bird. If you try to catch it, chances are you scare it away. Even if you succeed, it’ll just escape when you aren’t looking. The better way, then, is to work on your garden of life. The more your garden improves, the better chance there is for the bird to willingly land in it.

Cultivate all sorts of flora that the bird likes. There are some obvious ones, so just to name a few:

Eat-healthy-and-get-sufficient-sleep flowers. Excercise-and-break-a-sweat trees. Spend-time-with-people-or-things-you-love saplings. Put-your-phone-down-and-go-outside ivy. In essence, working on the garden is working on all aspects of yourself. And perhaps when you least expect it, there’d be happiness perching on one of the treetops.

An aside.

I can try to to image the bleak images that stem from depression—such is the power of human imagination and empathy—but I’ve always failed to fully understand it. I think chronically happy and chronically sad people are comparable to very different species. In college, there were a few years where I became very emotionally attached to some people who were later diagnosed with clinical depression. They’d seek some form of comfort from people around them, but they’d also have a “I don’t care about myself; why should you care about me” attitude that made it even harder not to care.

Once, someone I liked threatened suicide. I don’t pretend to know what was happening in their heads. Looking back, I think I just shut my emotions down because I did not know how to respond nor handle the relentless negativity that was being projected around me. Honestly, if it happened again, I probably still wouldn’t know what to do.

It took me some time to realize that I am not personally responsible for anyone else’s happiness. If you care about someone, you can try to help. But ultimately, there are things in life which we can only face alone, battles with inner demons and nightmares that the individual alone can fight.

That said, and this brings me back to the hedonometer, the average happiness for humans has been trending up the further we get from the start of the coronavirus, but has recently been trending down again. If you can manage your own happiness well in life, I’d like to encourage everyone to spread just a little bit of warmth to make the world a slightly happier place. While you certainly aren’t responsible for anyone else’s happiness, hopefully a little bit of kindness will go a long way and make the battles that those have to fight alone at least a little bit easier.

THE END.

E.C. should arrive any minute now. I have my notes in hand (this post), and I’m ready to face the music. Wish me luck. And yeah, happy birthday to me for turning into a quarter centenarian.